Water Management and Water Issues

By Peter Pinder and Nikhil Sriram

Masada National Park and the Dead Sea

Day six was filled with adventure for the group. After spending a restful night in a hostel in Masada, the group began the day with a tour of Masada National Park, spent some time at the Dead Sea, and ended the day with discussion and reflection on some of the history and water resource issues and solutions in modern and ancient cities of the region.

Masada National Park

The group’s visit to Masada, which means “Fortress” in Hebrew, was a fascinating combination of ancient history, challenges in water management, and natural beauty. Masada sits on top of a rock plateau and overlooks the Dead Sea. The fortress was originally built by King Herod of Judea between 37 and 31 BC. Masada is famous for being the site of a siege undertaken by the Roman Empire in 73 AD, led by commander Flavius, against 1,000 Jewish rebels known as the Sicarii, who were led by Elizar. Rather than submit to being enslaved by the Romans, Elizar convinced his people to opt for death, and it is believed that mass suicide was committed in the fortress, though archaeological evidence is unclear.

Image from the top of Masada, pathways

leading down the mountain can be seen, along with the Dead Sea in the background

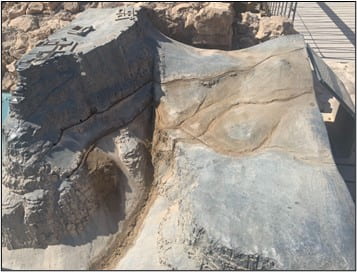

In terms of water management, Masada is quite unique. Masada’s only natural water source is flash floods, as the nearest spring is too far. As a result, the inhabitants of Masada designed elaborate systems to capture the water from flash floods through channels that flew into massive cisterns on the cliffside where water was held. From there, the water would be carried up to the fortress using donkeys and vassals. The pictures below show a model depicting the water channels related to Masada’s plateau location, as well as a cistern, which was utilized to store water for several months.

Model of Masada featuring the water channels that captured water from flash floods and stored it in cisterns

We were also able to draw connections to the religious and pleasurable uses of water when observing a Roman bath along with a Jewish mikveh, which we discussed in our previous blog surrounding our visit to Jerusalem. It reiterated that water carries importance not only practically but also ceremonially.

Overall, the visit to Masada National Park was excellent. Though it felt as though we were baking at times (even at 9 am, the sun was quite strong!), our tour guide Jordan was fantastic and highlighted the important connections to water present in Masada. Though it is now a tourist attraction and no longer a functioning fortress of the Judean empire, Masada still exemplifies the criticality of innovation in water management to promote sustainable access to water.

The Dead Sea

In terms of water resources, although the Dead Sea itself may not be a source of potable or industrial water for the populace it nonetheless illustrates the consequences and potential of anthropogenic water resource modifications.

The Dead Sea itself is the lowest land-based elevation point on earth (~400m below sea level at the water surface). This hypersaline body of water has a salinity concentration around 10 times greater than the world’s oceans, which was evident for trekkers as they easily floated above the salt crystals of the seabed while the solution delivered a slimy sensation to the skin of those curious enough to enter.

The Dead Sea, while beautiful, is in fact shrinking. Naturally this sea would be fed by the Jordan River; however, the growing population demands more water than the river can supply from the Sea of Galilee. While there are cries to save the Dead Sea, this natural phenomenon hides a resilience to extinction in the 306m depths in the north while also supporting the Israeli and Jordanian economies via mineral extraction and tourism in the southern ends.

While the Dead Sea may not be in danger of completely disappearing due to water resource management, changes in the aquifer composition have created an issue of sinkholes in the region leading to the loss of agriculture and infrastructure. Whether this is a reasonable price to pay for prosperity elsewhere in Israel or a focus of the future, it is in the hands of the Israeli water authority.

The Global Engineering Trek (GET) to Israel is jointly organized by the Northwestern Center for Water Research (NCWR) and the Israel Innovation Project (IIP). This program is focused on the topic of water (GET Water-Israel) and is offered to all first- and second-year Northwestern undergraduate students. GET Water-Israel is co-sponsored by McCormick Global Initiatives, the Institute for Sustainability and Energy at Northwestern (ISEN), the Crown Family Center for Jewish and Israel Studies, NCWR, and IIP.